Medieval Easter

Easter is here! Is your peacock re-feathered and dressed for Sunday dinner!

It is easy to view medieval times as a dreary, colorless life of drudgery and hard work at best, and warfare, torture, and deadly plagues at worst. A study of the holidays, however, spins the kaleidoscope and breathes color and joy into the picture, as well. Our modern vacation and feasting doesn't hold a flickering beeswax candle, much less a torch, to theirs! Christmas, for instance, was two weeks of feasting and celebration. Easter, Christmas, and Whitsunday (or Pentecost) were the three most important holy days of the year.

Feasting is an expression of joy, and to that end, it's important to remember Easter is a religious feast celebrating the miraculous event of a man rising from the dead after a horrific crucifixion. This event being the evidence that the long-awaited Messiah had walked among us, it is the very crux of the Christian faith, and therefore the most important day of the year, religiously. A popular current view of the medieval Church is of a grim and stern overlord. In contrast, however, John Chrysostom's Easter sermon, found at the Medieval Sourcebook, brims with joy and hope.

Are there any weary with fasting?

Let them now receive their wages!

If any have toiled from the first hour,

let them receive their due reward;

If any have come after the third hour,

let him with gratitude join in the Feast!

And he that arrived after the sixth hour,

let him not doubt; for he too shall sustain no loss.

And if any delayed until the ninth hour,

let him not hesitate; but let him come too.

And he who arrived only at the eleventh hour,

let him not be afraid by reason of his delay.

It's a world of beauty and wonder, he's saying! Join us! It's not too late, no matter what went before. This, of course, is something that both Shawn is coming to terms with throughout The Blue Bells Chronicles.

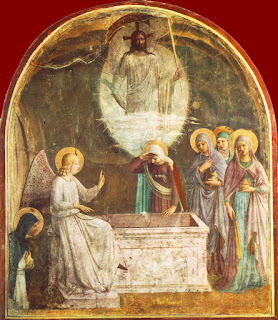

Like Christmas, Easter in the medieval world often involved plays, in this case depicting the angel at the empty tomb, and telling the Resurrection story. Similar to the Christmas creche, was the Easter sepulchre, dating back to at least the tenth century, and common all over Europe and Britain by the 16th Century. They were displays of sorts. They might be set in a small niche in a church or they might be extravagant wooden displays mounted atop tombs. Still others were free-standing. There might be brackets for candles, and carved depictions of angels or scenes of Christ's Passion.

The ceremonies surrounding these sepulchres involved responsories being sung while placing a crucifix and consecrated host in the tomb on Good Friday, surrounding it with candles and incense, and having either minor clergy or the sexton and his assistants watch the 'tomb' until Easter morning. At that time, the Host and crucifix were removed with much ceremony and processed around the church.

The feasting and celebration, of course, is a big part of what comes down to us, hundreds of years later. Maybe it is partly our fascination with what is so different from our time. The Easter message, after all, has not changed in all this time. Medieval and modern Easter sermons carry the same, eternal message: He is risen. Hallelujah. But we can hardly conceive, in our hasty modern world, of celebrating as they did.

Of course, to the modern world, giving up chocolate for 40 days is typical of Lent. To the medieval populace, with, metaphorically speaking, more churches and fewer grocery stores, seasons and religious belief made for a very different Lenten experience. The winter season offered little enough meat as it was. Lent, however, was a time of fasting from meat, dairy, and eggs. Fish might be the daily special for a full six weeks, with herring being particularly common--salted, says one site, and cooked with onions and cabbage. Mmm, good! Or, in the probably more accurate and less sarcastic words of one medieval boy: "Thou wyll not beleve how werey I am off fysshe, and how moch I desir that flesch wer cum in ageyn."

A medieval Easter feast, then, featured all the things that had been missing for so long, whether due to religious stricture or lack of grocery stores: meat, eggs, greens. More specifically, lamb, veal, rabbit, herbs. In case this wasn't enough meat, a medieval master chef also prepared a variety of birds for the table: swan, peacock, partridge, pheasant, blackbirds, pigeon, woodcock, sparrows, curlew and capon. A capon is a castrated rooster.

And the food was not just prepared for gastrointestinal delight, but to be aesthetic masterpieces. The peacock, for instance, would be stuffed and sewn back together, and served in full feathered regalia with its neck propped up and tail feathers fanned behind it. One article tells of a fanciful creature that might appear at the medieval table: the back of a pig joined to the front of a capon. When combined with such things as the Unicorn tapestry, mysterious myths of strange creatures and events, and the rich symbolism rampant at the time, it is a unique look into the medieval mind, perhaps full of mystery, romance, and possibilities beyond what they could see, to think of such things being created. Or perhaps it just makes some people squirm!

For those with a sweet tooth, the tansy was a favorite. It was something like a butter-fried pancake or omelette, flavored and colored with spinach, spiced with nutmeg and cinnamon, and flavored with cream. It vied with pain perdue (bread dipped in egg, fried, and topped with sugar, which sounds very like French toast), gilded marchpanes, and a form of gingerbread which involved honey, saffron and ginger baked into a biscuit. And for a society that did not have our regular access to candy and chocolate of all sorts, nuts and fruits also would have been a wonderful treat bursting from the barren winter back into their diets.

Dining in medieval days, of course, was not just about fueling the body. Without facebook, phones, or movies, feasts were a social and entertainment mega-event. The feast proceeded over many courses, with jugglers, minstrels, acrobats, and other entertainment, along with the chance to meet and greet.

Like today, medieval families often marked the day with new clothes, yet another sign of new beginnings. And of course, no Easter story is complete without mention of eggs. Even in medieval times, they were an integral part of the day. Children took eggs to church to be blessed, tenants brought eggs to their lords (a hen tithe so to speak), and kings dispensed gilded eggs to their underlings and favorites. Records survive of the Countess of Leicester purchasing eggs to distribute to her tenants in 1265. The number ranges from 1,000 to nearly 4,000. Edward I of England is said to have distributed 450 eggs, many covered in gold leaf, on his last Easter in 1307. (It's a safe assumption he didn't share any with Robert the Bruce.)

And now, after a day of alternately writing and hunting for my boys' Easter clothes, I am off to dye eggs--no gold plate here, I'm afraid--and buy a ham. It doesn't seem like much in comparison to a medieval Easter, but then, I have had plentiful meat these past few months, which they didn't. Still, maybe I can find feathers somewhere to stick in the ham, and call it a peacock.

Happy Easter!

COMING UP:

- April 29, 2017: I will co-host Food Freedom on AM 950 with Laura Hedlund and Karen Olson Johnson. Guests: Michael Agnew, craft beer expert, and Andrew Coons, Minnesota poet

- Listen to January's program: poetry and coffee beer

- Listen to February's program: Russian literature and Russian beer

- Listen to March's program: Irish beer with Tom Dahill and his new book Danny Who?

To learn more about my books, click on the images below.

If you would like to follow this blog, sign up HERE

If you like an author's posts, please click like and share

It helps us continue to do what we do

If you liked this article, you might also like

Medieval Easter Carols

The Medieval Christmas Season

or under the

MEDIEVAL EASTER or HOLIDAYS labels

The Medieval Christmas Season

or under the

MEDIEVAL EASTER or HOLIDAYS labels

Comments

Post a Comment